13.0 Reading and Writing Files¶

Data is usually stored in files, which can be organised in several different ways. Typically, some delimiter is used to separate the values and make the data easier for humans to read. A delimiter can be a newline character ('\n') or a space or a tab or a comma.

There are many different types of files. Some of the most common ones are text files, music files, video files, and so on. Text files contain only characters and can be easily opened on any computer that has a text editor (e.g., 'Spyder' is such a text editor; 'Notepad' and 'Word' are also text editors -- although you can't easily use them to write computer code). The Python programs you have been writting are text files -- the extension '.py' added at the end of their names is only needed in order for Python to recognise them. The other types of files (e.g., music and video files) include formatting that is specific to a particular file format, and in order to use such files you must have a special program that understands the corresponding format. In this unit you'll learn about reading and writing data to (mostly text) files.

13.1 Opening and reading files¶

If you want to open a file for either reading from or writing to it, you must tell Python where to find the files. By default, Python assumes that the file you want to use is in the same folder as the program that tries to access the said file (this is known as your current working directory, or 'cwd' for short).

To find your cwd, import the module os and use the built-in function os.getcwd():

import os

path = os.getcwd()

print(path) # I am NOT showing the output

Download from Brightspace the file 'sample.txt' and place it in your cwd. The code included immediately below opens this file and prints its contents on the screen:

# illustrates opening and reading a file:

# (as well as displaying its contents on the screen)

file = open('sample.txt','r') # open file + attach handle

contents = file.read() # retrieve all the info in the file

file.close() # close the file

print(contents) # disply what's in your file

The read() command will return the entire file as a SINGLE string if no arguments are passed (this string will include the newline character '\n'):

file = open('sample.txt','r')

file.read() # the raw output of the 'read()' function

file = open('sample.txt','r')

file.readlines()

file.close()

The last example illustrates the alternative function readlines() -- this returns a list containing the lines in the file. Note that each line is terminated with the newline character, so before you can use the info retrieved with this function you'll need to do some additional processing.

file = open('sample.txt','r')

lines = file.readlines() # stores a list

for line in lines: # traverse the list

print(line.strip()) # strip --> see Week6_Strings

file.close()

It is important to close the files after you are done with them, otherwise they will clutter your operating system, and you might end up with an error of the type: "too many files open". The preferred method for accessing files is by using a 'with' block, which has the following general syntax:

with <expression> as <variable>:

<block of statements>

Our example above would look like this:

with open('sample.txt','r') as file:

lines = file.readlines()

for line in lines:

print(line.strip())

# you no longer have to close the file "manually"

# -- its's done for you automaticaly

For the next example you'll need to download the file 'sample0_data.txt' from Brightspace. This file contains two columns of numbers. You can store the contents of the file in two lists (say); or, if you want, you can store the entire thing in a nested list. Let's do the former:

# initialize empty lists for storage:

first_col= []

second_col = []

# do the processing of the data stored in the file:

with open('sample0_data.txt', 'r') as file:

lines = file.readlines()

for line in lines:

items = line.strip().split() # removes unwanted characters, etc

first_col.append(float(items[0])) # update list 1

second_col.append(float(items[1])) # update list 2

print('\nFIRST_COL:\n', first_col)

print('\nSECOND_COL:\n', second_col)

13. 2 Numpy's built-in functions¶

In mathematical programming, the most common situation by far is needing to read a file containing numbers placed in various columns. Numpy makes the task of interacting with such file easier by providing a couple of built-in functions.

The first built-in is called loadtxt() -- which does exactly what it says.

For the next example, make sure you download the file 'sample_data.txt' from Brightspace and place it in your cwd (if you open the file with a text editor -- e.g., Notepad, you'll see that the first two lines are comments).

# the easy way to read numerical data.....

import numpy as np

a = np.loadtxt('sample_data.txt')

# print on the screen the result

# the file has about 100 rows of numerical data:

print(a)

Because the first two rows of the file start with '#' they are ignored by 'loadtxt()'. What happens if you have some lines at the top of your file, but they do not start with '#'? Easy: use the optional keyword skiprows in the call to the function 'loadtxt()'. For example:

import numpy as np

a = np.loadtxt('sample_data.txt', skiprows=90)

# print result on the screen to convince yourself

# that Python did skip many rows....

print(a)

If we are interested only in certain columns of data, we can directly save those columns into suitable one-dimensional arrays:

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

a = np.loadtxt('sample_data.txt', skiprows=0)

x = a[:,0] # this is the 1st column

y = a[:,1] # this is the 2nd column

# maybe you want to plot x and y....:

plt.plot(x, y, 'r')

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.ylabel('y')

plt.title('First Plot')

plt.show()

# maybe you want to plot only every other 4th point in your arrays

plt.plot(x[::4], y[::4], 'bo')

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.ylabel('y')

plt.title('Second Plot')

plt.show()

The 'loadtxt()' function allows us to do this in a neater way: You can use the keyword usecols to specify which columns you want to read, where the index starts at zero for the first column (here we have only 2 columns in our data file, but this syntax can be applied to more complicated, multi-column files). Here's how we do it:

import numpy as np

x, y = np.loadtxt('sample_data.txt', skiprows=90, usecols=(0,1), unpack=True)

# check to see x and y:

print('x= ', x)

print('y= ', y)

# compare with the numbers we displayed earlier on the screen

The unpack parameter, if set 'True', transposes the returned arrays, allowing a statement of the form x, y = loadtxt(...) to be used. You can find more about the 'loadtxt()' function on the official page of the NumPy module:

https://numpy.org/doc/stable/reference/generated/numpy.loadtxt.html

If you want more control over how your data file is read, the NumPy function genfromtxt()' is particularly useful. You can learn about this by visiting the official website (that goes beyond the scope of this introductory module):

https://numpy.org/doc/stable/reference/generated/numpy.genfromtxt.html

13.3 Writing text and numbers to a file¶

As already discussed above, you can open a file for writing using the syntax:

<file_handle> = open('<name_of_file>', 'w')

where the pointed brackets indicate names that you are free to choose: 'file_handle' is just any variable name that you'll use to refer to your opened file, while 'name_of_file' is the name you give to the file that will be opened for writing. If the file does not exist, it will be created. Remember that it is customary to specify an extension for your file. If you store data, '.dat' is a good extension, for text you can use '.txt'. Of course, you can store numbers in a '.txt' file, but it makes more sense to distinguish between files that are meant for storing numerical data and text files. Another extension used often for files that store numbers or text is '.out'.

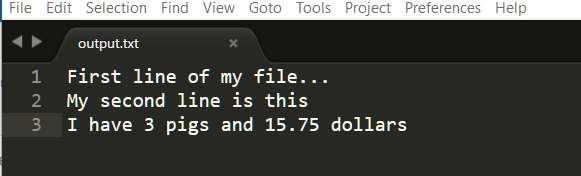

# simple example that illustrates writing to a file:

# open file and assign handle to it:

fid = open('output.txt', 'w')

# start writing to your file:

fid.write('First line of my file...\n')

# start adding other lines....:

fid.write('My second line is this\n') # note the newline character

# ... and yet another one:

fid.write('I have {} {} and {:4.2f} dollars'.format(3, 'pigs', 15.75343534))

# remember to close the file:

fid.close()

# in case it is not obvious: we have written both text and numbers

# it is preferable to use a 'with' statement,

# which automatically closes the file after

# the enclosed block of code finishes executing:

with open('output.txt', 'w') as fid:

fid.write('First line of my file...\n')

fid.write('My second line is this\n')

fid.write('I have {} {} and {:4.2f} dollars'.format(3, 'pigs', 15.75343534))

# the output will be EXACTLY as before

# the upshot is that you don't have to worry about forgetting to close the file

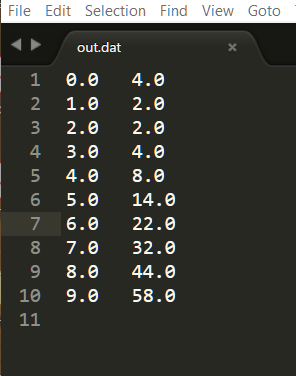

In the example included below we create two numerical arrays: one that contains ten numbers ($0.0, 1.0, 2.0,\dots, 9.0$), and another one corresponding to the values of the function $y = x^2-3x+4$ at those particular points. We want to store these numbers as two columns in a file (each row containing an $(x, y)$ pair).

# illustrates how to write numerical data to a file

# such data is usually stored in columns

import numpy as np

x = np.arange(10.) # a set of x-values

y = x**2 - 3*x + 4 # the y-values of some function of 'x'

fid = open('out.dat','w') # open file 'out.dat' for writing

for i in range(len(x)):

fid.write("{} {}\n".format(x[i],y[i])) # add one row at a time

fid.close() # when done, close the file

We can re-formulate the code in this example by using list comprehensions:

# Two other alternatives to the writing to a file code:

import numpy as np

x = np.arange(10.) # a set of x-values

y = x**2 - 3*x + 4 # the y-values of some function of 'x'

#------------------------------------------------------------------------

# alternative v.1

fid = open('out1.dat', 'w')

[fid.write("{} {}\n".format(x[i], y[i])) for i in range(len(x))]

fid.close()

#--------------------------------------------------------------------------

# alternative v.2

with open('out2.dat','w') as fid:

[fid.write("{} {}\n".format(i,j)) for i, j in zip(x,y)]

# the output of both versions will be the same as above

# the only difference is that the names of the files will be different

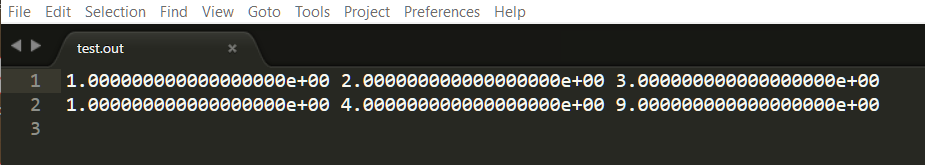

NumPy comes with a handy built-in function called savetxt() which makes it very straightforward to save an array to a text file. Here is a basic example:

import numpy as np

x = np.linspace(1, 3, 3) # array: [1., 2., 3.]

y = x*x # array: [1., 4., 9.]

np.savetxt('test.out', (x,y))

The output is saved to a file containing the $x$-values on the first line of the file, and the $y$-values on the second line of the file, with all values by default printed in exponential format to machine precision, which is NOT convenient.

We can write our arrays in columns by including 'np.transpose((x,y))' as an optional parameter in the call to savetxt(), and we can also format our data to the appropriate number of significant figures by including the fmt keyword argument (obviously, 'fmt' stands for 'format').

# modified version of the code immediately above

import numpy as np

x = np.linspace(1, 3, 3) # array: [1., 2., 3.]

y = x*x # array: [1., 4., 9.]

np.savetxt('test_new.out', np.transpose((x,y)), fmt = '%5.2f %5.1f')

# transposing a rectangular array (M rows and N columns) amounts to swapping

# the rows and the columns: ROW #1 becomes COL #1, ROW #2 becomes COL #2, and so on.

# The result will be a new rectangular array that has N rows and M columns

If you want to include header or footer lines (with some explanatory text), you can do this by passing strings using the keywords header and footer. The example included below uses the former keyword:

# modified version of the code immediately above

import numpy as np

x = np.linspace(1, 3, 3) # array: [1., 2., 3.]

y = x*x # array: [1., 4., 9.]

hdr = "This is my first data file" # add some text in the header:

np.savetxt('test_new.out', np.transpose((x,y)), fmt = '%5.2f %5.1f', header=hdr)

The output of this code is included below:

# you can add multiple line comments at the top of your file:

import numpy as np

x = np.linspace(1, 3, 3) # array: [1., 2., 3.]

y = x*x # array: [1., 4., 9.]

hdr = "This is my first data file\n" # note the newline character

hdr += "Columns: x, y" # add an extra line in the header

np.savetxt('test_new.out', np.transpose((x,y)), fmt = '%5.2f %5.1f', header=hdr)

13.4 Plotting curves from a data file¶

When you spend a lot of time running numerical simulations, you'll want to store some of that data from your simulations into one or more text files; this is done by what we have discussed in the previous section. Of course, you stored the data so that later you can plot it again using Matplotlib. So, how exactly are you going to do that? Here is how:

# for this example you'll have to download the file 'out3.dat'

# from Brightspace and place it in your working directory (so that Python can find it)

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

X, Y = [], []

for line in open('out3.dat','r'):

values = [float(s) for s in line.split()]

X.append(values[0])

Y.append(values[1])

plt.plot(X, Y,'r', X, Y,'ro')

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.ylabel('y')

plt.title('Red bumpy parabola')

plt.show()

# same as the above example, but avoiding the list comprehension:

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

X, Y = [], [] # initialize X and Y as empty lists

for line in open('out3.dat','r'):

values = line.split() # this returns a list -- see Week6_Strings

X.append(values[0])

Y.append(values[1])

plt.plot(X,Y,'g')

plt.xlabel('x')

plt.ylabel('y')

plt.title('Green parabola...')

plt.show()

REFERENCE:

T. Gaddis, Starting out with Python (Fourth Edition), Pearson Education Ltd., 2018